2002-11-21 20:27 UTC

Tag Soup: How UAs handle <x> <y> </x> </y>

HTML user agents have to be able to cope with invalid markup, such as unclosed tags, tags closing in the

wrong order, and tags where they aren't allowed, if they are to render the existing Web. Rendering the existing

Web is rather critical, because if you fail to do so, no user will adopt you. (A Web browser that can only load

Dive Into Mark and the W3C site

isn't much good to anyone.)

Unfortunately, the HTML specification does not define how to handle invalid markup. (XHTML does, because it

uses XML, which goes to great lengths to define how to handle invalid markup. This is one of the best features

of XHTML as far as most Web weenies are concerned — it forces pages to be syntactically correct!) Because

it is undefined, Web browsers have each had to invent their own way of handling invalid content, while all

trying to get the effects that are similar enough that users will think all is fine.

Let's take an example of invalid markup:

<body>

<p>This is a sample test document.</p>

a <em> b <address> c </em> d </address> e

</body>

How would you represent this in the DOM? This is not a trivial question. The DOM was designed to cope with

well-formed documents, it has no facility for coping with elements that are half in another and half out of it.

(And nor should it — after all, such documents are invalid.)

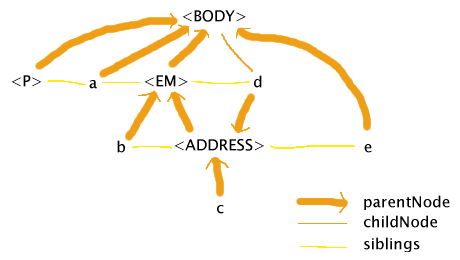

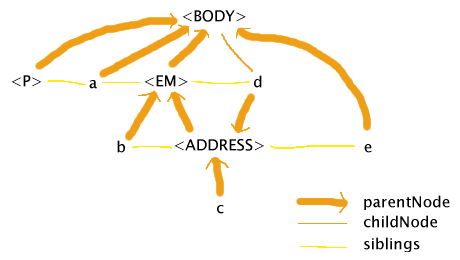

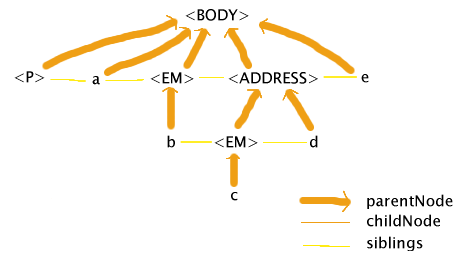

WinIE 6 tries to faithfully represent what the author wrote, to the point of making the

DOM itself ill-formed, as described below. (Note that whitespace nodes and the text node child of the P

element have been ignored for simplicity.)

This DOM quite close to what the author wrote — e is indeed a sibling of the ADDRESS element while

being a child of the BODY element, and d is indeed a sibling of the EM element while being a child of the

ADDRESS element. That d is a child of the BODY is, I think, an artifact of IE trying to get the second half of

the ADDRESS element to be under the BODY while the first half is under the EM.

This DOM is probably showing us a lot more about the internals of Trident (WinIE's layout engine) than was

intended. An implementation that internally uses a tree (which is basically what you need to correctly do CSS2)

would be hard pressed to come up with a DOM like this.

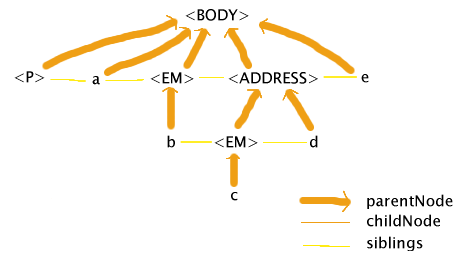

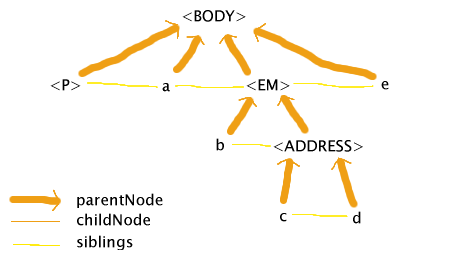

Mozilla 1.2, on the other hand, tries to get the same effect, but without deviating from

the rules of the DOM, namely that it has to be a tree:

The main feature of this treatement is that it has two EM nodes. Mozilla reaches the ADDRESS start tag and

realises that EM elements cannot contain ADDRESS elements, so it closes the EM and reopens it inside the

ADDRESS. Except in certain edge cases (like borders, explicit inheritance, and which selectors match which

elements), the result of styling using CSS would be the same as in IE.

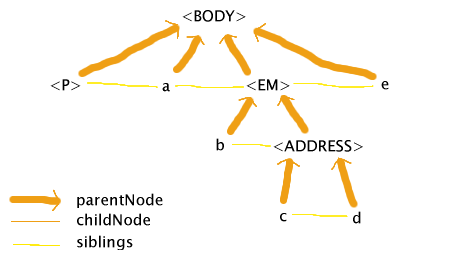

Opera 7 Beta has yet another interpretation. It attempts a mixture of the Mozilla and IE

attempts: it tries to keep the DOM valid while not letting any of the elements in the document map to more than

one node in the DOM:

The basic principle at work here, it appears, is that the markup is fixed up by delaying any closing tags

until after all other open elements have been closed, and no attempt is made to make the DOM follow the HTML

DTD. So in this case, the ADDRESS element keeps the EM element open until its end tag. Opera's DOM is not the

full story, though, as even though Opera puts the two text nodes (c and d) under the same element in the DOM,

it still styles only the first text node (c) as if it was in the EM. (To some extent. It appears that

some styles are propagated, and not others.)

The advantage of the techniques used by IE and Opera is that it makes it easier to cope with styling and

scripting invalid markup. If you use the DOM to dynamically alter the EM element in IE's case, for instance,

it'll happily affect the element throughout, around both b and c. In Mozilla's case, an attempt to change the

EM element would only affect one of the parts at a time, so for example adding a border around the first EM

would not put a border around text node c. Opera achieves the one-to-one mapping of markup to element as well,

but doesn't restrict the EM to the text nodes that it contains in the markup.

The approaches used by Mozilla and Opera, though, get you a much more stable DOM. This is important for

scripting: if you try to walk IE's DOM, you are likely to hit an infinite loop, because walking up the chain of

parents for d (namely d → ADDRESS → EM) and then going to the next sibling will bring you straight

back to d.

Mozilla's candid nature (what you see in the DOM is exactly what it's going to style) makes

interpreting its results a lot easier. Opera's approach (providing a DOM but styling a slightly different

model) is a lot more confusing.

The net result is that each model has its advantages and disadvantages, and they are about equally matched.

And since HTML leaves this undefined, all of them are correct.

If you are interested in examining this further, I based this article on the results I obtained using a client side DOM browser I wrote

and my legacy HTML parsing test 004

(which is not really a test, since there's no "correct behaviour"). That test also throws styling into the mix

(I touched on this above). Amusingly, if you compare Mozilla's behaviour on tests 004 and

005 you find an obscure bug that has nothing to do with the

markup being invalid (the colour changes even though the only difference is that 'font-variant' has been

changed to 'font-weight').

Pingbacks:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

The distinguished Mark Pilgrim was the first

to come forward as possibly

having a perfect Web log, although he admitted to having a few known issues.

While you read this site review, bear in mind that it is purposefully intensely

pedantic. As my own site demonstrates, I'm coming from

the view that complying to the spirit of the specs to be a lot more important than

what

a page may look like in famously broken

browsers like Windows IE 6 and earlier.

Enough of the disclaimers, though. On with the review:

- XHTML

The whole document validates

as XHTML 1.0 Strict, which is a cool.

text/htmlOf course, I have to mention the

fact that Mark is sending his XHTML page as text/html. Why not send it as text/html to

IE, and application/xhtml+xml to everything else? This is roughly what Xiven does,

for instance.

- More MIME types

The main page is not the only page sent with the wrong MIME type, unfortunately.

The FOAF file is sent as text/plain,

while it should be some XML variant. This is especially noticable because the <link>

element pointing to that file claims its MIME type is application/rdf+xml.

Similarly,

the <link> element pointing to the RSS feed says its MIME type is application/rss+xml

but it is actually the controversial text/xml. (Which causes another problem — what is the character set of the RSS feed?

Per RFC3023 (section 3.1, paragraph 3) it's US-ASCII but

per the XML declaration in the file, it's UTF-8. Thankfully in this case it doesn't really matter since

all the codepoints in the file are common to both encodings.)

While we're on the subject, I'll just

quickly add that the MIME type of the JS file (text/x-javascript) doesn't match the MIME type

used in its <script> element (text/javascript) either.

<div id="logo">This element appears to be there purely for stylistic reasons — it doesn't add anything to the structore of the

document. As such, it should be removed.

Actually, <div>s are a pain. At the moment

(i.e. in the pre-XHTML2 world), they are basically serving two roles: section delimiters (the <section> element

in XHTML2) and presentational hooks for CSS (the <div> and

<span> elements in XHTML2).

Section delimiting is fine, but adding hooks for presentation into a supposedly semanticly marked-up document is

very dubious. Unfortunately, CSS2 has very limited abilities for adding stylistic hooks to content (the :before,

:after, :first-letter and :first-line pseudo-elements are about it) and the

technically correct solution (using XSLT to add the hooks on the client side) is a pain.

My rule for whether a <div> is semantic (delimits a section) or presentational (only there

to be used from CSS) is pretty simple. Does the block start with a header and then have content? Or, if not, would the block still

make sense if you added a header to it? If the answer to either question is "Yes" then the <div> is legitimate,

otherwise you should look for ways around it.

In this case, the <div> is definitely presentational, since all it contains is the page header (which

is correctly marked up using an <h1>).

<span id="logoleft">Well, in theory, <span>s with just a class or id are as bad as <div>s. However,

I don't see any way around it, and indeed I use <span>s myself for exactly the same reason, so nevermind!

<span class="divider"> </span>Mark assures me that this is to get around a bug in Bobby,

a tool used to detect accessibility problems on a site. This is silly! You should not make your page less compliant to the

accessibility guidelines just in order to appease a buggy tool.

In fact, several of the uses of <span class="divider"> </span> on Mark's site actually

make the page harder to read using Lynx and other non-CSS browsers.

I would recommend removing them all and complaining to the Bobby team.

<a class="skip" href="#startnavigation">Jump to navigation</a>This needs to be marked up as a paragraph. If it wasn't for the <div>,

which as mentioned above really should be removed, this would be invalid. Other than that, though,

this is a great aid to accessibility. For instance when browsing this site with Linx it makes

finding your way around the site a lot easier.

<div id="wrapper">, <div id="main">These are redundant. A case could be argued for keeping one of them (it's the main content "section")

but there is no doubt that at least one of them should be removed, since they exactly shadow each other.

The name of the outer one's id is a giveaway too.

- Redundant titles

This is a very minor nit, but I noticed that the permalinks have titles set on both the link, and the link

label (an image). Since the image itself is not the permalink, I would suggest removing its title attribute.

The alternate text is well chosen, however, conveying exactly the same as the image. Indeed, I'd say the

image is harder to understand than its alternate text! (I had to examine the square box to get its tooltip before

I realised what it was for.)

<p class="firstparagraph">That class attribute doesn't add anything, especially now that CSS has a

:first-of-type selector.

<cite>dive into mark</cite>Fine use of an often misunderstood element.

’Good use of U+2019, the preferred character to use for apostrophe

.

<p></p>Empty paragraphs are disliked by the HTML specification.

This is almost certainly caused by an over-zealous CMS, in which case

it is a good example of why CMS systems have to be very carefully designed, and are not simply an alternative to writing accessible

markup!

<p class="categories"> This non-breaking space is extraneous, and doesn't add anything valuable to the content (what does a word consisting of just a space on its own

mean?). It's not entirely clear to me why the space is needed here, so I presume it is to work around some obscure browser bug.

Note that in this case, the single link is in a paragraph of its own, as I suggested the "Jump to navigation" link should be.

This is good.

<span class="divider">[twisty.com] </span>Normally I wouldn't even mention something like this, but I'm pretty sure it's not what was intended, and I wasn't really sure

what was. The problem here, basically, is that I don't think the class is correct. How is the domain a divider? One could also argue

that the content of the span is redundant, since it's information that is already stored in the link.

There are some other cases of strange use of the "divider" class in the menu section.

<div class="center"><div class="hr" title="Lorem ipsum is a harsh mistress"><hr /></div></div>Wow! This is probably the worst line of the entire page. First, class="center" is presentational markup in disguise. The class should be made semantic ("divider" might actually

be correct in this case). Second, the inner <div> is redundant (like the wrapper/main <div>s above).

Third, the class of the inner <div> is redundant, since it is just a repeat of its contents. Fourth, the <hr>:

Since this page is marked up using <div>s as section markers, it makes little sense to also use <hr>s.

I'd recommend removing the entire line, and using <div>s to mark up the days instead.

<a name="startnavigation" id="startnavigation"></a>This appears to be redundant with the previous non-blank line, which also sets an id. If it's important

to stick with <a name=""> markup, then it should preferably be wrapped around the header on the next non-blank

line (think about what the element, as written, means: the start of the navigation is an empty string).

Overall, this is a very well designed site, with most of the problems appearing to be conscious decisions to work around bugs in

software, rather than mistakes. The stylesheets are very well written, with pixels only used in the very few legitimate cases,

ems and percentages being used elsewhere, colours and backgrounds specified together, and so forth. The markup is

semantically rich, presentational markup is avoided except in a few cases, and many accessibility features are well used.

This site will probably not be the most valid, semantically rich, no-presentational-markup, strictly compliant Web log

of this challenge, but it is definitely a top contender.

The next site I'll be examining is Aaron Swartz's Web log.

Pingbacks:

1

2

3

4