2002-11-21 20:27 UTC Tag Soup: How UAs handle <x> <y> </x> </y>

HTML user agents have to be able to cope with invalid markup, such as unclosed tags, tags closing in the wrong order, and tags where they aren't allowed, if they are to render the existing Web. Rendering the existing Web is rather critical, because if you fail to do so, no user will adopt you. (A Web browser that can only load Dive Into Mark and the W3C site isn't much good to anyone.)

Unfortunately, the HTML specification does not define how to handle invalid markup. (XHTML does, because it uses XML, which goes to great lengths to define how to handle invalid markup. This is one of the best features of XHTML as far as most Web weenies are concerned — it forces pages to be syntactically correct!) Because it is undefined, Web browsers have each had to invent their own way of handling invalid content, while all trying to get the effects that are similar enough that users will think all is fine.

Let's take an example of invalid markup:

<body> <p>This is a sample test document.</p> a <em> b <address> c </em> d </address> e </body>

How would you represent this in the DOM? This is not a trivial question. The DOM was designed to cope with well-formed documents, it has no facility for coping with elements that are half in another and half out of it. (And nor should it — after all, such documents are invalid.)

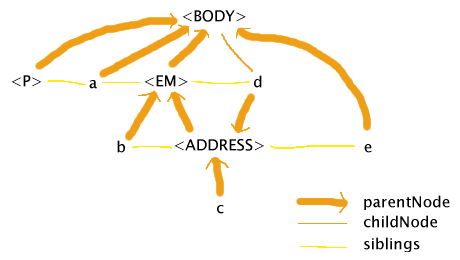

WinIE 6 tries to faithfully represent what the author wrote, to the point of making the DOM itself ill-formed, as described below. (Note that whitespace nodes and the text node child of the P element have been ignored for simplicity.)

This DOM quite close to what the author wrote — e is indeed a sibling of the ADDRESS element while being a child of the BODY element, and d is indeed a sibling of the EM element while being a child of the ADDRESS element. That d is a child of the BODY is, I think, an artifact of IE trying to get the second half of the ADDRESS element to be under the BODY while the first half is under the EM.

This DOM is probably showing us a lot more about the internals of Trident (WinIE's layout engine) than was intended. An implementation that internally uses a tree (which is basically what you need to correctly do CSS2) would be hard pressed to come up with a DOM like this.

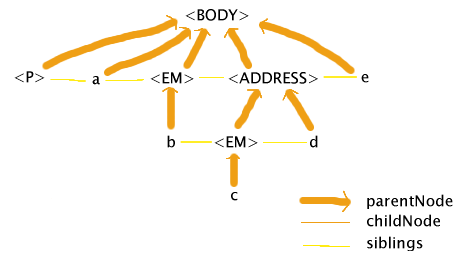

Mozilla 1.2, on the other hand, tries to get the same effect, but without deviating from the rules of the DOM, namely that it has to be a tree:

The main feature of this treatement is that it has two EM nodes. Mozilla reaches the ADDRESS start tag and realises that EM elements cannot contain ADDRESS elements, so it closes the EM and reopens it inside the ADDRESS. Except in certain edge cases (like borders, explicit inheritance, and which selectors match which elements), the result of styling using CSS would be the same as in IE.

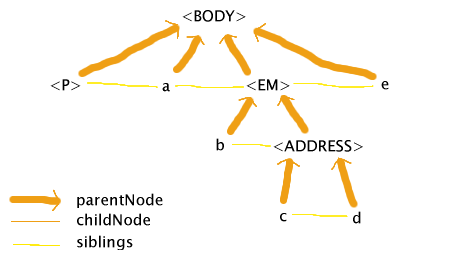

Opera 7 Beta has yet another interpretation. It attempts a mixture of the Mozilla and IE attempts: it tries to keep the DOM valid while not letting any of the elements in the document map to more than one node in the DOM:

The basic principle at work here, it appears, is that the markup is fixed up by delaying any closing tags until after all other open elements have been closed, and no attempt is made to make the DOM follow the HTML DTD. So in this case, the ADDRESS element keeps the EM element open until its end tag. Opera's DOM is not the full story, though, as even though Opera puts the two text nodes (c and d) under the same element in the DOM, it still styles only the first text node (c) as if it was in the EM. (To some extent. It appears that some styles are propagated, and not others.)

The advantage of the techniques used by IE and Opera is that it makes it easier to cope with styling and scripting invalid markup. If you use the DOM to dynamically alter the EM element in IE's case, for instance, it'll happily affect the element throughout, around both b and c. In Mozilla's case, an attempt to change the EM element would only affect one of the parts at a time, so for example adding a border around the first EM would not put a border around text node c. Opera achieves the one-to-one mapping of markup to element as well, but doesn't restrict the EM to the text nodes that it contains in the markup.

The approaches used by Mozilla and Opera, though, get you a much more stable DOM. This is important for scripting: if you try to walk IE's DOM, you are likely to hit an infinite loop, because walking up the chain of parents for d (namely d → ADDRESS → EM) and then going to the next sibling will bring you straight back to d.

Mozilla's candid nature (what you see in the DOM is exactly what it's going to style) makes interpreting its results a lot easier. Opera's approach (providing a DOM but styling a slightly different model) is a lot more confusing.

The net result is that each model has its advantages and disadvantages, and they are about equally matched. And since HTML leaves this undefined, all of them are correct.

If you are interested in examining this further, I based this article on the results I obtained using a client side DOM browser I wrote and my legacy HTML parsing test 004 (which is not really a test, since there's no "correct behaviour"). That test also throws styling into the mix (I touched on this above). Amusingly, if you compare Mozilla's behaviour on tests 004 and 005 you find an obscure bug that has nothing to do with the markup being invalid (the colour changes even though the only difference is that 'font-variant' has been changed to 'font-weight').

Pingbacks: 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27